BBA Artist Prize 2021

About the 2021 edition

Now in its 6th year, the BBA Artist Prize honours talented artists. Together with an international jury, Berlin-based BBA Gallery has selected 20 artists for the shortlist, whose works can be seen in a joint exhibition in the Kühlhaus Berlin from June 24 - July 4. The first prize winner will receive a solo exhibition in BBA Gallery.

Meet the artists

Jonathan Kraus (Germany) receives the Leuchtturm1917 Award for his portraits which . The 3rd prize was shared by Nina K. Ekman (Germany) for her sculptures that investigate the unsustainability of our modern lifestyle, and Daniel Paul (Czech Republic) for his sculptures that focus on critical social agreements reflected in issues such as religion, gender, racism, war, etc. The 2nd prize was awarded to Tom Price (UK) for his sculptures that study the dialogue between two contrasting materials and their negotiation for space and identity. And finally: The 1st prize goes to Sven Windszus from Germany for his interactive digital art works that make you question everything.

20 Shortlist artists

-

Kings & Queens in Their Castles has been called one of the most ambitious photo series ever conducted of the LGBTQ experience in the USA. Over 15 years, Atwood photographed more than 350 subjects at home across the United States, including nearly 100 celebrities. With individuals from 30 states, Atwood offers a window into the lives and homes of some of America’s most intriguing and eccentric personalities. Modern day tableaux vivants, the images portray whimsical, intimate moments of daily life that shift between the pictorial and the theatrical. Alongside creatives such as artists, fashion designers, writers, actors, directors, music makers and dancers, the series features business leaders, politicians, journalists, activists and religious leaders. It includes those who keep civilization running, such as farmers, beekeepers, doctors, chefs, bartenders and innkeepers. Some miscellaneous athletes, students, professors, drag queens and socialites. As well as a cartoonist, barista, poet, comedian, navy technician, paleontologist and transgender cop. Also showcased are urban bohemians, beatniks, mavericks and iconoclasts, many of whom blossomed in the 1960s and 1970s but seem to be slowly disappearing.

-

Mairead Dunne’s work explores the role of model-making in contemporary art, shifting between intimate photographic viewpoints and site-specific installations. Adapting elements of theatre and illusion, the work combines a mixture of found and fabricated materials conveyed as a series of miniature tableaus. The imagery is built up through layers of glass applying early animation effects and shot using experimental photographic techniques. Working across several different mediums, the work’s distinct aesthetic can be attributed to the artist’s background in painting, anchoring the work in representations of her former medium.

The work considers ideas such as the celestial, transience, isolation, and the photographic metaphor ‘the passage from darkness to light’. These ideas are forged within the physical spaces of the work - within the rocks, and the water, and the many reflections that define its illusory environment. This photographic series examines the etymology of the word Grotto, derived from the Greek word Kruptos, meaning secret or hidden. A grotto is a natural or artificial cave containing a smaller chamber or cavern. In mythology, grottos are considered to be mystical or sacred spaces, and those with a water source bring fertility and life. In Catholicism it is believed that apparitions of the Virgin Mary appeared at the Grotto of Massabielle, in Lourdes. Transcending the physical and metaphorical stages of the grotto, this series explores themes of Fertility, Passing and Rebirth. A portal to a strange new reality - shifting from its fertile opening, to what lies beyond.

-

There is authenticity in low-resolution imagery. This is how Bigfoot, UFO, and Loch Ness Monster videos uploaded to YouTube gain their validity. Similarly, the most powerful still and moving images from conflict and occupied zones are often low-resolution, heavily pixelated, and blurred. In researching this project, Graves began to realize how fundamental the pixel is in allowing us to cross borders in real-time through the emission and instantaneous reception of visual signals (live streaming webcams, security cameras, and mobile footage from protests, war zones and dangerous journeys). He wanted to embrace this quality—which enabled him, from Mexico City, where he was undertaking a residency—to capture beachgoers at leisure using a networked surf camera above Coolum Beach, Australia. The uncanniness of the images—at times the people documented appear more mythical than human—belongs to a politics of fear and threat of otherness (the pixelated face of a criminal, Bigfoot, fighter jet footage of an airstrike, or CCTV footage). These things sit at the intersection of digital and physical, and the real and imagined, where the spectacle trumps direct experience of the world, and things we recognise start to blur seamlessly into places and things that aren’t real.

-

Juliette Losq’s work describes the borderlands at the edge of human habitation. Reclaimed by nature, these regions become refuges for wildlife, dens for children, and spaces of speculation on what might have gone on before and what may be occurring out of sight. As part of her working process Losq produces paper landscapes inspired by historical optical devices such as the paper peepshow. These are used as maquettes from which to make drawings, paintings and installations. Though based on real places, these landscapes become fictional through their construction. Through this process of reconstruction and reinterpretation, she aims to preserve the ephemerality of the sites, whilst developing an understanding of the model as a partially imagined, partially ‘real’, space that can transport the viewer conceptually from one place to another. The installation drawings play with this idea that the viewer is able to gain a spatial experience of a site that they are at a remove from, whilst smaller, two-dimensional works create a self-contained world that seeks to absorb the viewer. Alluding to the Picturesque and the Gothic of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Losq interweaves their motifs and devices with the marginal areas that she depicts, evoking an uncertain world hovering at the edges of a symbolic ‘Clearing’, where wilderness and chaos oppose civilization and order, and in which beauty and neglect are interchangeable.

-

‘Synthesis’ is the title of a body of work Price has been developing over several years. It is the study of a dialogue between two contrasting materials - resin and tar - and their negotiation for space and identity when forced to become a single unified entity. What appear to be petal-like inclusions are actually cracks and fissures created through a careful manipulation of the catalysing process of the resin. They cluster around and interact with amorphous, invasive bodies of tar, which loom - apparently suspended in space. Heat from the exothermic curing process of the resin causes the tar to expand and look for pathways through the cracks as they open within the resin. The tar initially appears densely black, almost light absorbent, but upon closer inspection, intense hues of jade, turquoise and gold are revealed on the surfaces of the cracks where the tar is illuminated.

These works sit somewhere between sculpture and painting. The outer shape is undeniably sculptural but the inner forms and colours are more like a three-dimensional abstract painting. The general composition - layers; intensity; concentration and placement of different elements – is carefully planned in advance, but ultimately much is left to chance. The final result of this collaboration between artist, material and chemical reaction is only truly revealed as the work nears completion.

Price explains that the use of chance as a tool for his creative process allows him to overcome the limits of his own imagination and produce works that are as fresh and surprising to him as they are to others.

-

(Together) Alone is in equal parts the result of an inner conversation and the beginning of a continuing dialogue with the material, the viewers, and all those who feel inspiration for their own in light of the artwork. The installation of RGB White tubes and an expansive steel structure owes its existence to the shift in perspective from the headlines and hashtags that would have to be dealt with to the materials that, for Sandra E. Blatterer, have recognition value and necessity. Without the certainty of one’s own (artistic) vocabulary, any (isolated) statement would be worthless.

Instead, the authentic construction allows all viewers to immerse themselves in the artist’s encounter with her material and savor the isolated, reduced situation of being alone with the installation. In a world characterized by the expansion of virtual spaces into thing-reality, relationships and bonds are lost in the flow of information and simulations.

(Together) Alone is physical in its own way. As an object, it protrudes toward the viewer. In its dimensions, it requires and initiates movement around it to access all perspectives. Its simplicity and directness leave much free space and generate questions rather than answers. We have already learned to adapt our senses to the pace of simulation reality. What comes up short are lasting images; not to mention the self-made images in our head.

With the luminous bodies from a bygone era, their serial assembly, their immediate experience, Sandra E. Blatterer leads the viewer into the now, into the here. All the sensory thrills, all the spatial, even quasi-physical presence of the installation express themselves as a homage to the time spent with the artwork. A homage to the “contemplative dwelling with things, the unintentional seeing that would be a formula of happiness,” as Byung-Chul Han says.

Text and theory: Thomas Schütt

-

Reflecting a life which is both culturally Japanese and American, Mayuko Ono Gray’s graphite drawings hybridize influences from traditional Japanese calligraphy combined with Western drawing practices and aesthetics. Growing up in Japan, every Saturday afternoon was spent with her Sensei, a calligraphy master. At high school, in preparation for the entrance exam to art university she took private lessons to learn drawing with graphite and charcoal, practicing techniques such as chiaroscuro and sfumato. Traditional Asian art-forms have often integrated word and image, and her interest and practice follow this path in a unique way. She mostly uses images of persons, animals, and still life captured in daily experiences. A Japanese proverb accompanies each work, spelling out the hiragana and kanji characters intertwined to create a single line which has only one entrance and one exit. The calligraphic line begins at the top right and ends toward the bottom left of the page, following traditional Asian writing. The single line going through a pictorial plane is a metaphor of a life: one entrance as birth of physical body, and one exit as death and loss of physical body, and all the complicated experiences during physical existence between these two.

-

‘Mutant’ aims to fulfil, explain, and show his desires and dreams that have met obstructions, due to societal expectations of his gender. Growing up in Korea, Dae always felt as if he was a mutant, an aberration from the heterosexual norm. He decided to turn shame into pride, by making mutants that proudly display his hitherto secret desires. As a man, he has always felt he is inferior in terms of beautification. So when he is designing these mutant objects, he represents himself with objects that are usually considered uninteresting and inferior and mutates them into ones that are grandiose and superior to encourage people to consider the implicit boundaries around gender that exist in different cultures and societies around the world.

-

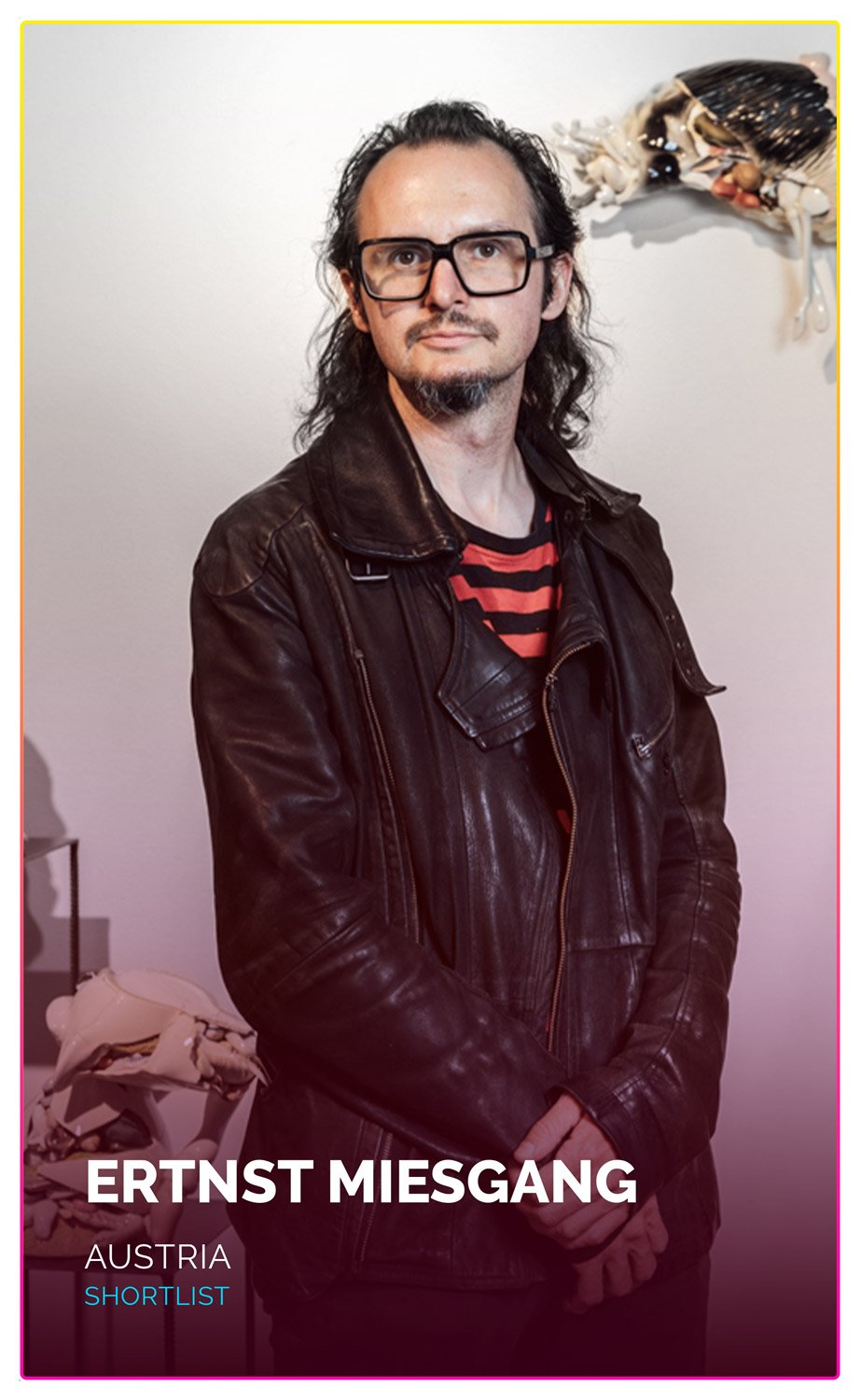

The sculptures of Ernst Miesgang’s series ‘Shattered’ pretend to be anatomical models. On a closer look they quickly turn out to be pure fantasy products. They consist entirely of porcelain and ceramic shards glued together with epoxy resin. Much of Miesgang’s work can be read as a satire on scientific models and concepts with which he criticises the excessive belief in progress of our time. Without a radical social paradigm shift, the problems of our time - be it advancing social inequality, the climate crisis or currently the global health crisis - cannot be solved. Therefore we as a society have to rethink our value system. Speed, volume and growth must not be the focus of interest. Miesgang’s works, some of which he has worked on meticulously for months, are a plea for slowness, contemplation and reflection, which he often misses in the hectic art world.

-

(With his artwork ‘Lebensraum’, Sven Windszus would like to invite each participant to use their own muscle power to control the growth of our species. He has reduced the real conditions we are facing to a form of physical experiment. The problem of overpopulation, the resulting destruction of our living space and the steady rise in sea levels, have been put into a visual context. Pressing on the pump causes heads to appear. If too many heads are pumped up, the available space expands, but the rising water level problem worsens. Just a few movements of the pump should make it clear to participants where this experiment is headed. The question is: how do we deal with this responsibility – do we keep pumping and see more and more heads pushed under the water or do we halt the process before this can happen? In his work, Windszus wants to engage with the phenomenon that, although we have recognised the problem of overpopulation, this realisation is not usually reflected in our actions. ‘Don’t press the button’ plays with the childlike curiosity in us to do something forbidden. The particular attraction of this is as old as Eve’s biblical seduction of the forbidden fruit. In Windszus’ work the thrill of doing something wrong is symbolized by a single button. This button restricts the viewer’s options for action. Either we look at the image on the display and we leave it as it is for now or we try to influence it by pressing the button.

The physical distance between the screen and the button makes it easy for the viewer to take influence. The scenery on the screen suggests a negative outcome. A simple press of a button could satisfy the curiosity without any consequences. The certainty that you have done something wrong will dissipate in the form of a pink cloud of exhaust gas. The thrill has won.

-

Accelerated Intimacy considers questions of site, memory and staging in relation to time. A parallel to her previous methods of compositing and reconstructing documented images; Choo re-presents fragments through time, in the format of an interactive and immersive installation. Through appropriating film scripts, the artist decontextualized conversational lines and significant quotes; in turn, reconstructing a potential narrative surrounding each character.

All 5 subjects, shot in various hotel rooms, are given the liberty to interpret parts of film scripts and re-enact specific roles within a set. The dual presentation of images and objects creates a complex staging of ‘lived’ experiences that exist concurrently across time and space. Rather than offering any kind of resolution to histories of the characters and site, Accelerated Intimacy is a culmination of carefully constructed coincidences that are unfinished and ongoing; revealing and establishing complex relations with each reading.

-

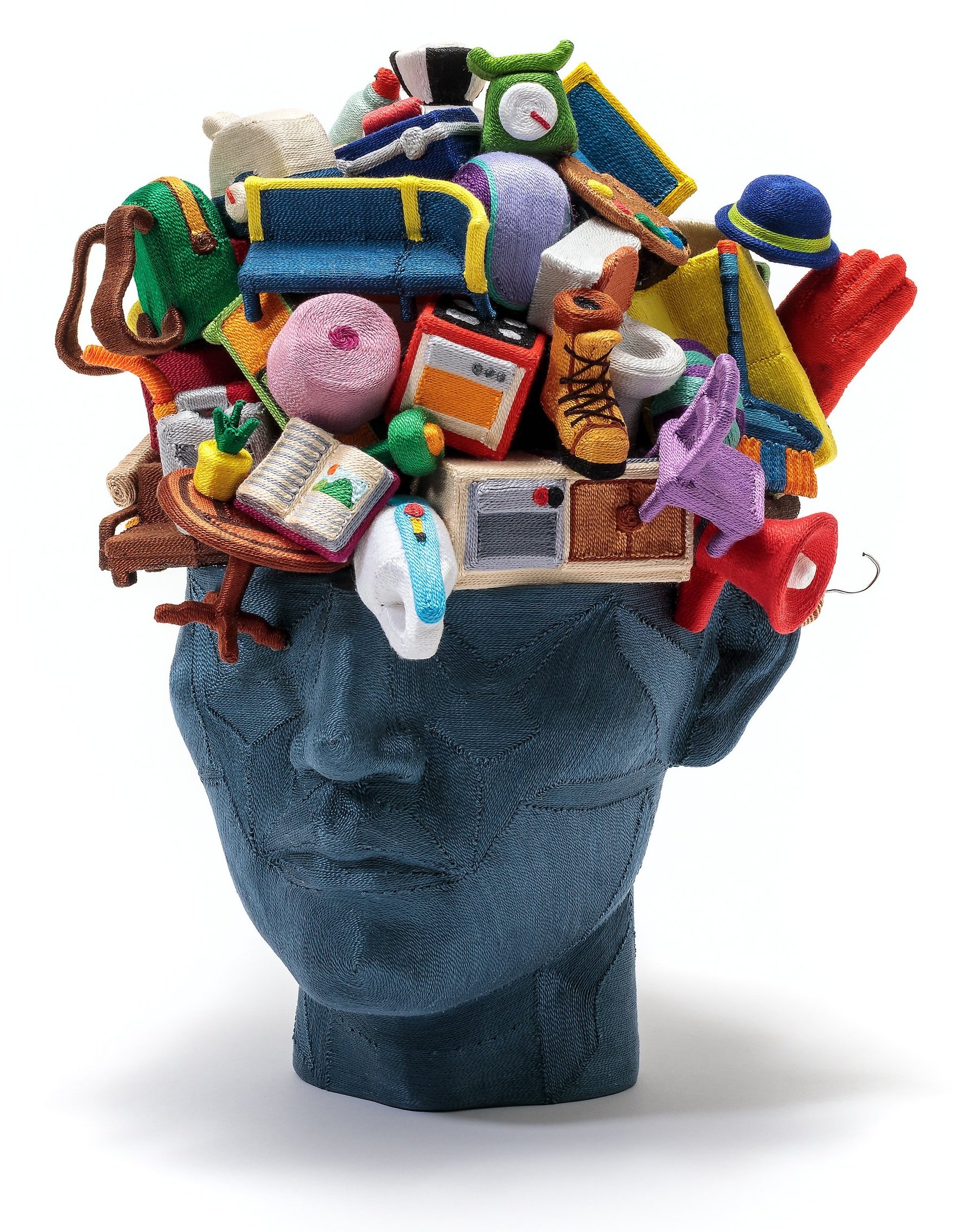

Nature and questions of human relations are recurring sources of inspiration and subject matters in Ekman’s work. The connection to nature is deeply rooted in Ekman as the North of Norway has been a backdrop throughout her childhood. Her relationship to nature is not only a personal longing, but a point of interest which has unfolded the topic of nature’s role to man and vice versa.

Most recently Ekman has been drawn by the technique of tufting as a way of building textile sculptures. Tufting is a method of weaving carpets, but to Ekman tufting has become a playful opportunity to create singular pieces with an original appearance. The molding, handling of needles, yarn and textiles are essential to Ekman’s fascination with tufting - the physicality of the process. At first sight the tufted works might appear as simply fun, likeable and quirky, but most of Ekman’s pieces investigate the unsustainability of our modern lifestyle inviting the observer to reflect upon our linear way of consuming, fast fashion and the consequences of our neglect for the future of the planet.

Sustainability and circularity are also key in Ekman’s work production by the choice of materials, when Ekman excess yarn from the textile industry to create her pieces. The dilemmas and paradoxes of modern life and the preservation of our globe are a driving force in Ekman’s work - urgent and inevitable, but the tufted huggable cactus and vivid palm trees are also somehow comforting utopias.

-

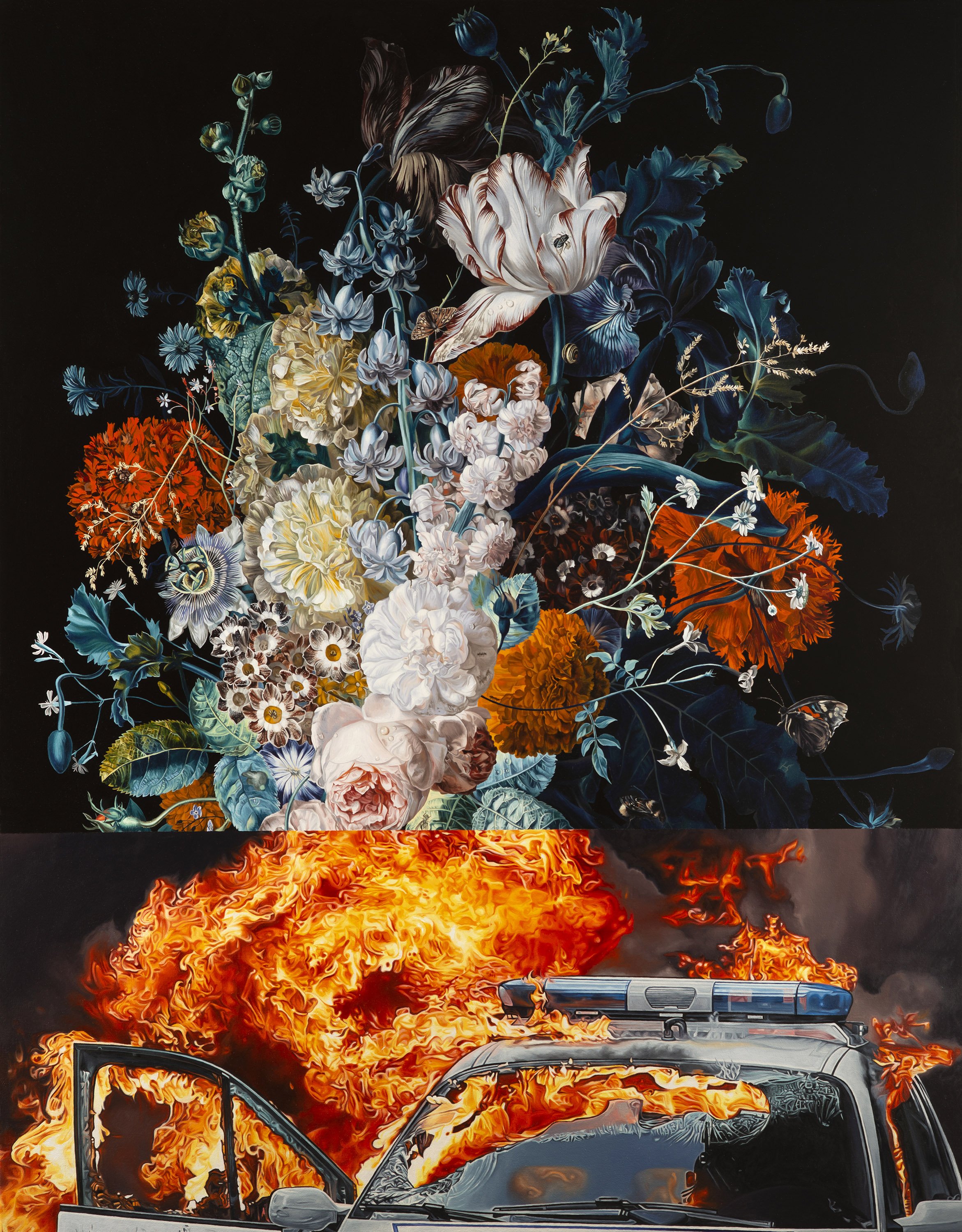

The recombination of art history and contemporary art can be both, a commentary on the respective references and on the present, an homage as well as criticism. ‘In the conservatory’ by Édouard Manet for example may probably be one of the greatest paintings at Berlins Old National Gallery. But on the other hand, how enervated does the woman in this painting look and why? Thus, the paintings are partly observations and partly statements, sometimes even in written form. If a young artist decides to write something on a painting, what would that be? Besides a signature or a date, of course. Roy Lichtenstein for example did a painting in 1962 just showing the three letters ART, captioning it ART, selling it as a piece of art and by doing so he pretty much represents the Pop Art style of using commercial art’s techniques for fine art paintings while making a move that is as bold as the letters on his painting.

So what’s next, young artist? How to catch up with a painting that is almost 60 years old? In preparation for the BBA Artist Prize Jonathan Kraus thought about the classic stock excuse ‘I was young and needed the money’ commonly used for your youthful follies. He transferred the proverb-like excuse to ‘I am young and need the money’ (in German: Ich bin jung und brauche das Geld), a phrase, which may fit for almost every young artist. Replacing a submissive looking dog in Georges Clairin’s 1876 portrait of the famous actress Sarah Bernhardt by a nude of himself could reveal itself as the kind of thing about which he would later say: ‘Yeah, I was young and needed the money.’

-

Thematically, the cycle Turbofolk focuses on critical social agreements in which the boundaries of ethics come into close contact with the limits of the law, increasingly reflected in social issues such as religion, gender, racism, ecology, power, freedom, war, etc. This moralistic challenge is a crucial contribution to the reflection of today’s consumer-oriented world. The author ironizes people’s connection to fleeting events rather than to more profound experiences and points out the inevitable phase of our society’s mind that, by its action, forms a parasitic organism. The fundamental construction element of the content is the symbol and its method of processing. Just as a sentence is composed of words and words of letters, the message comes from understanding the meaning of individual words and their relationship. The statue becomes a free interpretation of the fictional story through a collage of symbols used. However, the author does not use symbols in the normative and generally established sense. For example, the word “priest“ does not necessarily express legal or religious status but can be understood as a tool representing authority. The leitmotif of each sculpture is a direct conflict between two or more moral positions, each position depending on a certain subjective point of view of the viewer. Complete understanding, that is, fluent perception of context, multi-layeredness, and ambiguity of topics, can only distort our own point of view, namely in its own relation to the symbol and the emotional attachment to the content.

The formal part of the work is created using a computer and a classic craft approach. The concept is designed in a virtual software space, enabling a very dynamic creative work process, regardless of the need for workshop space and the necessary modeling material.

Then the model is transferred from the virtual space to reality using CNC machines and then processed by classical technological procedures, such as grinding, painting. The approach to the sculptural figure is directly based on the centuries-old tradition of sculpture, which connects the figure with the pedestal both in terms of technology and content.

-

Chris Tille’s art is the key to a special form of perfection and elegance. It is about shapes and lines, order and beauty. It`s about making invisible truths visible. The magic behind creation, in a truly cosmic sense: his specialty is the science of astronomy - and he transforms it into art. ‘Big Bang’ is a depiction in graphite grey, with wave-shaped lines rushing out from the dark depths, coming at the observer. What you are looking at is the signature of the big bang - sound waves transformed into light and recorded on photographic paper. The very birth of the universe, captured in complex clusters, sharpened into a work of art. For his works, Tille speaks to researchers and is given gigantic packages of data by the Max Planck Institute. It`s all about the collision of black holes, gravitational waves and the visualisation of cosmic occurrences. Tille spends month sitting in front of his computers transforming original sound documents from space into meticulously calculated graphic structures. The result: in his works, galactic events become visible and literally flow towards the observer - the language of the stars in the form of modern art freed of all embellishment.

-

The photographs of Ewa Cwikla have something disturbing, dark, baroque in them. They are unusual, capricious, far removed from the expectations associated with today’s portrait photography. Her composition of the photographs is determined by the dialogue with the art of the Dutch and Flemish Golden Age. Her images are inspired by her genuine admiration and understanding of this trend in painting as well as of the atmosphere of the 17th century Netherlands, which she absorbed while visiting Dutch museum collections and cities permeated for centuries by the spirit of the great masters. The photographs of Ewa Cwikla are distinguished by the perfection of a studio arrangement, an almost mathematical precision in setting the artificial light, which is once focused on a chosen motive, and elsewhere scattered, flowing from several sources.

-

Shawn Fitzgerald is a creator and performing artist who emphasizes humanity, both awful and sublime, in his work. He makes dance-theatre performances for stage and film that investigate human emotion through movement and that reflect on issues of current social relevance.

Au Mur de la Mer is a duet that follows the inevitably intertwined rumblings of two humans. Set against the raw landscape of coarse cliffs and green-algae coated boulders at Pas-de-Calais, France, Au Mur de La Mer imagines regret as a frontier borrowed from our own future. The duo stumbles, soaked and soiled, through fading remnants of Hitler’s terrifying Atlantic Wall at Cap Gris-Nez. They pull and tear at one another, crudely easing the other’s fall and helping each other stand once more. Set to the natural soundscape of the cold ocean tide and howling autumn wind, and featuring the striking and solemn Astrid Sweeney and Jonas Vandekerckhove, Au Mur de La Mer leaves us with one eye full of sea water, the other eye full of sand.

-

June Lee’s work focuses on the individual in contemporary society today. Lee explores the neutrality and duality of the individual as a distinct unity and again as a constituent of the collective society. In particular, she sheds light on the social phenomena surrounding the individual in contemporary social space, especially on negative conditions such as bystander effect, mass psychology, scapegoating, and biases. Using East Asian element of the thread, which represents human life, to form human figure-like works, her art looks at the problems of the modern man from a third-person perspective.

-

Working with salvaged musical instruments, amateur choirs, marching bands, urban bat colonies, flocks of grackles, and pedicab fleets, Steve Parker gathers people into democratic, communal ceremonies that explore systems of social behavior, their variability across history, and their application to contemporary life.

Ghost Box is a playable sound sculpture modeled after a WWII era short wave radio. When touched, the sculpture plays different looped audio clips of coded transmissions, including Morse Code, spirituals, the Hebrew Shofar, and the Iron Age Celtic carnyx. Embedded into the sound sculpture are a series of musical scores on paper that incorporate maps and icons of the WWII Ghost Army, the functional wires of the attached electronics, and map pins. A ghost box is a communication tool used by paranormal investigators to speak to the dead. Typically, a ghost box is a modified portable AM/FM radio that continuously scans the band. It is believed to create white noise and audio remnants from broadcast stations that entities are able to manipulate to create words and even entire sentences.

-

Born in Melbourne, Fiona White is a highly acclaimed Sydney-based artist and global practitioner whose work tackles issues at the forefront of international political discourse. Fiona’s deeply expressive and thought provoking works are inspired by people from all corners of the globe, including Australia, the Americas, Africa and Mexico. A passionate storyteller, White fuses history and the current international climate, drawing from a range of photographs, media, the internet, and her fantastical imagination to narrate her stories.

The signature charcoal faces claim the foreground of her colourful works, and are the central figures of her worldly, yet familiar scenes. An expansion from traditional portraiture, the decidedly human characters inhabit strange, collaged narratives, interspersed with scrambled symbols and landscapes, challenging our understanding of what it means to be a citizen of the world.

White’s distinctive and vibrant character work manifested from an early age, her layered painting style reflecting the multi-faceted nature of her practice. A self-taught artist, Fiona’s impressive command over a range of media, developed by experimenting with drawing cartoon cut outs from magazines and papers, which over time evolved into the intricate mixed media works she produces today.

Jury spotlight

40 made the longlist

Tom Atwood

Simon Averill

Thijs Biersteker

Sandra E. Blatterer

Dongyan Chen

Sarah Choo

Federico Cuatlacuatl

Ewa Cwikla

Mairead Dunne

Nina K. Ekman

Ingri and Fredrik Fiksdal/Floen

Shawn Fitzgerald

Viktor Freso

Kailum Graves

Mayuko Ono Gray

Clemens Gritl

Dae uk Kim

Jonathan Kraus

June Lee

Sai Lev

Juliette Losq

Ernst Miesgang

Tobias Molitor

Anne Moses

Steven Parker

Daniel Paul

Rachel Peachey

Nikolina Petolas

Henri Prestes

Tom Price

Regner Ramos

Xuemei Ren

Jake Scharbach

Fukiko Takase

Chris Tille

Elizabeth Tremante

Ira Upin

Fiona White

Sven Windszus

Anja Wülfing